CS247 Lecture 10

Last Time: Git, UML, Inheritance This Time: virtual, override, pure virtual, destructors

How do we know which method call in the hierarchy is invoked for b.isHeavry() or b->Heavy()?

(Notes copied into Virtual Method)

- Is the method being called on an object? If so, always use the static type to determine which method is called.

Book b{...}; // b.isHeavy() -> calls Book::isHeavy()

Text t{...}; // t.isHeavy() -> calls Text::isHeavy()

Book b = Text{...};

b.isHeavy(); // calls Book::isHeavy()- First example: In the first example,

b.isHeavy(), the objectbis of typeBook, and sinceisHeavy()is a non-virtual method, the method called is determined by the static type ofb, which isBook. Therefore, it callsBook::isHeavy(). - If we call

t.isHeavy(), exhibits dynamic dispatch. Dynamic dispatch, also known as runtime polymorphism, is the mechanism in C++ by which the appropriate method to be executed is determined at runtime based on the actual type of the object being referred to. This is achieved through the use of virtual functions and the virtual function table (vtable). When you callt.isHeavy()wheretis an object of theTextclass, the method that gets executed depends on the actual type of the object, which isTextin this case. SinceisHeavyis declared asvirtualin the base classBookand is overridden in the derived classText, the method call is dynamically dispatched to the version ofisHeavydefined in theTextclass. - In the case of

Book b = Text{...};, theisHeavyfunction call onbwould indeed call theBook::isHeavy()method. This is because the dynamic type ofbisBookeven though it was originally assigned aTextobject. This scenario demonstrates the principle of using the static type to determine which method is called.Text{...}creates aTextobject. TheTextobject is used to initializeb, which is of typeBook. This involves a process called object slicing, where only the base class part of the derived object is used to initialize the base class object. Whenb.isHeavy()is called, it’s based on the static type ofb, which isBook. Sincebis of typeBook, theBook::isHeavy()method is called. Even thoughbwas originally created as aTextobject, the static type determines which method is called, and it calls the version ofisHeavydefined in theBookclass.

When a method is called on an object, the determination of which method to invoke is based on the static type of the object.

- Is the method called via pointer or reference?

a. Is the method NOT declared as

virtual? Use the static type to determine which method is called:

Book* b = new Text{...};

b->nonVirtual(); // calls Book::nonVirtualb. Is the method virtual? Use the dynamic type to determine which method is called:

Book* b = new Text{...};

b->isHeavy(); // calls Text::isHeavy()We can support:

vector <Book*> bookcase;

bookcase.push_back(new Book{...});

bookcase.push_back(new Text{...});

bookcase.push_back(new Comic{...});

for (auto book: bookcase){

cout << book->isHeavy() << endl;

}Each iteration calls a different isHeavy() method.

What about

(*book).isHeavy()?

(*book),isHeavy()calls the correct version/method as well. Why? Because*bookyields aBook&(i.e. a reference).

What is the purpose of the override keyword?

- It has no effect on the executable that is created! (WHAT DOES THAT MEAN????????)

- However, it can be helpful for catching bugs.

class Text {

...

bool isHeavy();

}isHeavy() is missing a const. This won’t override Book’s virtual isHeavy because the signatures do not match.

Specifying override will have the compiler warn you if the signature does not match a superclass’s virtual method.

Compiler will always choose to call a const method to guarantee optimization and correctness.

Why not just declare everything as

virtualfor simplicity?Declaring

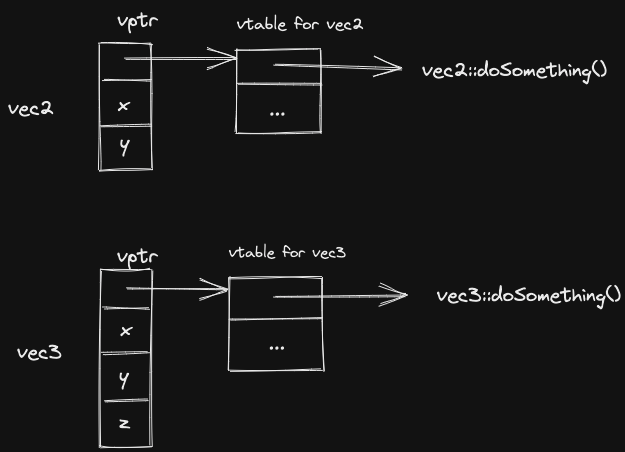

doSomethingas virtual doubles the size of our Vec object, program consumes more RAM, slower in general. This extra 8 bytes is storing the vptr - virtual pointer. vptr allows us to achieve dynamic dispatch with virtual functions.

struct Vec{

int x, y;

void doSomething();

}

struct Vec2{

int x, y;

virtual void doSomething();

}

Vec v{1,2};

Vec2 v{3,4};

cout << sizeof(v) << endl; // 8 bytes

cout << sizeof(v) << endl; // 16 bytes- Declaring

doSomethin()asvirtualdoubles the size of our Vec object. Program consumes more RAM, slower in general. - This extra 8 bytes is storing the

vptr- virtual pointer.vptrallows us to achieve dynamic dispatch withvirtualfunctions.

Remember: In MIPS, function calls use the JALR instruction, it saves a register, jumps PC to a specific memory address, hardcoded in the machine instruction.

With dynamic dispatch, which function to jump to could depend on user input. Cannot be hardcoded.

struct Vec2{

int x, y;

virtual void doSomething();

}

struct Vec3:public Vec2{

int z;

void doSomething() override;

}

string choice;

cin >> choice;

Vec2* v;

if(choice == "vec2") v = new Vec2{...};

else v = new Vec3{...};

v->doSomething(); Depending on the dynamic type of the v

Depending on the dynamic type of the v vptr it will call Vec2 or Vec3’s doSomething().

When we create a Vec2 or Vec3, we know what type of object we’re creating, so we can fill in the appropriate vptr for that object.

vptr always points to the vtable which points to the function address.

Now, in either case, we can simply follow the vptr, get to the vtable, and find the function address for the doSomething() method.

Extra running time cost in the time it takes to follow the vptr and access the vtable.

C++ philosophy: Don’t pay for costs unless you ask for it.

Destructors Revisited

class X{

int* a;

public:

X(int n): a{new int[n]}

~X() {delete[] a;}

};

class Y:public X{

int* b;

public:

Y(int n, int m): x{n}, b{new int[m]}

~Y() {delete[] b;}

};

X x{5};

X* px = new x{5};

Y y{5,10};

Y* py = new Y{5,10};

X* pxy = new Y{5,10}

delete px; delete py; delete pxy;Which of these leaks memory?

Because the destructor is non-virtual, for pxy, we invoke ~X , not the ~Y, so this array b is leaked, since the Y object does not get destroyed.

Solution: declare virtual ~X();, so delete pxy will call ~Y().

Unless you are sure a class will never be subclassed, then always declare you destructor virtual.

If you are sure, enforce it via the final keyword.

class X final{

...

}Now, the program won’t compile if anyone tries to subclass it.

Object destruction sequence:

- Destructor body runs

- Object fields have their destructors run in reverse declaration order

- Superclass destructor runs

- Spare is reclaimed

Next: CS247 Lecture 11